Interview with Lex Braes for ArtSlant

Feb. 2012: Lex Braes is a Scottish-born, New York-based artist, working mostly with paint. His work, which spans over three decades, has been exhibited widely in both Europe and the US. His most recent show closed on February 26th, at the new gallery space Show Room on the Lower East Side, and was, according to the artist, his best work since 'Still' (1998). The artist's work can be seen at the National Academy's The Annual 2012 group exhibition, open until April 29.

I talked with Lex while he was in Munich, finishing a commission, about his return to the fore, painting, and the influence of the city.

Charlotte Jansen: Paint as a medium has fallen in and out of fashion. It now seems to be gaining popularity, once again, at least in the UK, where I'm based.

Is that the case in New York? what does it mean to be a painter today? Why should people return to it in our digital age?

Lex Braes: Painting is an inner necessity for me and for the survival of our culture. It's fundamental source is a means for discovering reason and always will be that. A good painting lives on, can offer possibilities for understanding ourselves in a way other media cannot. I like that it does it quietly. It's emotionally important to me, it continues to surprise and inform me in how to live better, and more. It survived the camera; it'll survive the digital revolution too. I'm not really concerned about trying to convince people to do things. Painting exists; artists find it because of the necessity in them.

CJ: Your native Glasgow has a strong reputation within contemporary art. You've been based in New York for most of your life. How have the cities shaped you?

LB: Life changes you anyhow, the place I suppose to a degree and the people you connect with more than any physical environment have influenced me. NY suits me, a north Atlantic light and an obvious extension of European culture, which I feel connected to; maybe it's the Scottish principles of the enlightenment that I feel exist here. I feel alive in NY in a healthy way; there is a psychic environment as well as physical and both seem to work for me, for the moment at least.

Glasgow as some cultural mecca? Hmm I don't think I'd fit in but I'd love to be wrong about that.

Aside from two exhibitions with Richard Demarco at the Edinburgh Festival in '86 and '88 I've never shown my work in the UK. Don't get me wrong, I'd love to, but no one has asked.

I'll probably always be a Glaswegian at heart; I am very fond of 'my ain folk,' and growing up in Castlemilk was an incredible experience that I wouldn't wish to change. I still break into song for no apparent reason whatsoever so yes I belong to Glasgow, still.

CJ: How do you work? How to approach and piece and how long does it take?

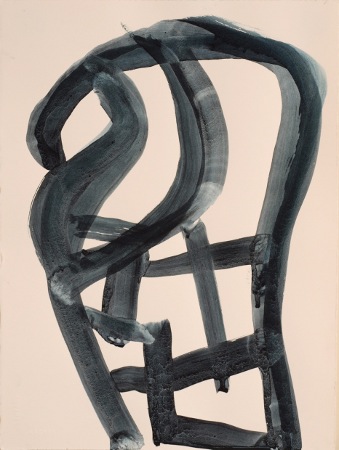

LB: At this stage there's usually a predominant motif that I'm involved with; in the run up to the present show it was a pre-Columbian statue from Nicaragua, well a part of it at least. I had been looking at this newspaper photo, pinned to my wall since 2004 and about six months ago, quite suddenly I knew what to do with it, I don't know why. I keep a mental file of images and from many hundreds of drawings one will surface; it's an ongoing process. There's no hurry; it all comes out if I can just let it. One relates to another in ways that make sense without my trying to control the sense; it's a fine balance of will and unwilling. One painting can take many years to discover and another months; the small brush drawings which are part of my vital daily practice, can be resolved in one sitting or they too can carry over in time to months and even years--so scale and medium doesn't really change the outcome.

CJ: Who buys your work?

LB: Ha, hardly anyone that's who! But seriously, I have been fortunate with private collectors in Europe and the US. I owe an immense gratitude to several who are from collector families. I'm fortunate to call some of them my friends but they would not want me naming names as they really are not interested in publicity.

CJ: In an interview with Karen Wilkin you describe yourself as 'a painter from perception even while my improvisatory meanderings away from the subject's representational reality may obfuscate this fact.' Can you elucidate this further?

LB: I said that huh? Well I think that what I'm really after is painting a moment in time, the moment that I am first engaged with the subject, whatever that physical reality may be, e.g. melted snow making a strange architectural shape on a tiled roof in Germany. Well I'm not after the physical reality as such, but the visual language contained in the encounter with the physical world. Also very much interested in how and why this happens to me, how I can elucidate or express and communicate this phenomenal experience. That this event happens at all, between me and whatever it is that has grabbed me and stops me in my tracks and holds me in a contemplative state. It's the encounter I'm interested in; what key is there? Can I capture its essence?

CJ: Your current show is a presentation of paintings that runs alongside video works by Allan Kaprow and Shōji Hamada. is this a new way of viewing your work?

Do you think you will expand into new media in the future?

LB: I am very happy with the underlying concept of introducing other media and aesthetic sources. My pottery teacher studied with Hamada in Japan and I became acutely aware at a young age of non-Western aesthetics; this connection never left me. Later I studied with Allan Kaprow at UCSD, and he introduced an intellectual framework towards the craft. I had always held craft as the purest and so highest of disciplines, so for me to bring together these two seemingly disparate inspirational disciplines or ways of making beauty, I could see was radical to a polarized art world. Where a schism exists between craft and concept. I knew Allan to be a brilliantly gifted, natural painter when almost no one else in the art world had any inclination of his particular aesthetic heritage. In the mid-1990's Dick Bellamy and I talked at length about Allan's early paintings. For me the heritage is critical. Again like my source imagery, I'm trying to get underneath, to see the truth in the structures we live by and in this way my work is philosophical, takes perception seriously and not at all as some dumb retinal knee jerk response but a response considered thoroughly and engaged with intellectual rigour. Like the Kaprow happenings, at first glance a random chaotic affair on further analysis is a fully perceived idea broken down into parts in order to convey his profound understanding of art and how to engage with life. Both artists have continued to influence me. In this way the inclusion is my homage, my respect to both great artists, to masters of their craft.

I have made works in relation to theatre in the past. Two weeks ago I made drawings to an improv dance routine; this kind of interactive creative work interests me more than say using different media myself.

CJ: Is pain necessary for painting? The physical act of painting on such a scale is quite violent, or at least, demanding...

LB: Yes. Painful experience is a necessary part of life; painting or cleaning floors, there's no escaping it. We must accept it and we must use it; we need to work with our feelings, what we can learn from feelings. It's all about transformation and staying real. There is an over indulgence in society now to escape reality, with an abundance of tv 'reality,' more and more ridiculous notions of what reality is or may be. Maybe one of the fortunate aspects of living in a metropolis like NY is that tv is less relevant; there is too much interest on the street and with surviving daily life instead.

CJ: What would a typical day for you be?

LB: Rise early, feed the cat, get down to work--it's a job as well as a necessity!

CJ: What does the future hold?

LB: Well without a crystal ball no one knows, but I don't think I'd want one either. Howsabout: more, please, and to live to see my beautiful daughter grow up into a happy independent woman?

-Charlotte Jansen